What’s in a name?

If you could ask the humble zircon, the answer might be mistaken identity and decades of undeserved obscurity.

In the Victorian era, the peak of popularity for zircons, a mined mineral, colorless ones were regularly used as diamond alternatives and blue ones were particularly popular.

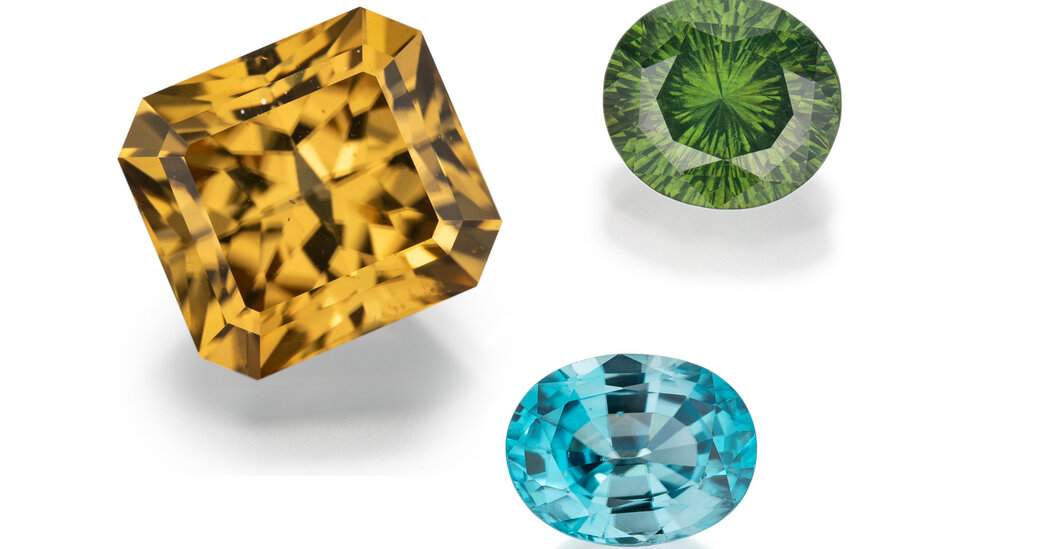

“Zircon can come in a wide range of colors — blue, yellow, brown, green and, rarely, a purplish-pink color,” said Nathan Renfro, senior manager of colored stone identification at the Gemological Institute of America. “They also have quite a high luster and a high degree of dispersion; as the light travels through the stone, it’s divided into its component colors, so you see flashes of reds and blues and greens,” a phenomenon commonly referred to as fire.

Then, along came cubic zirconia, an inexpensive synthetic crystal discovered in the 1930s but not developed to the point it could be faceted until 1969. By the end of the 1970s, it bypassed zircon and became the most common diamond simulant.

But the public had become confused, believing that zircon and cubic zirconia were similar, if not actually the same material. “People associated the name zircon with a cheap imitation,” Mr. Renfro said.

Today, there is evidence that the record on zircon is finally being set straight. The ranks of independent designers who have responded to its charms are growing, and the gem appeared alongside diamonds and traditional precious gemstones last summer in the high jewelry collections of major houses such as Louis Vuitton and Buccellati.

The latter brand, for example, included several designs featuring blue zircons in its 36-piece Mosaico collection. “These stones,” Andrea Buccellati, its co-creative director, wrote in an email, “have colors and cuts that give us designers free rein to our inspiration by creating more modern and innovative products.”

Svend Wennick, a principal at the Danish gem dealer Wennick-Lefèvre, said he was not surprised that prestige jewelers were now using zircons. “Looking at zircons brings out a passion for the gemstone because they’re so beautiful,” he said, although he added that, to maximize their appearance, “the polishing and the cutting are really important.”

And clients do give established brands the latitude to present unfamiliar or undervalued gems, Mr. Wennick said. “Their brand value is high,” he noted. “They don’t have to justify the price of the jewelry by the gem.” So once clients have an open mind toward the stones, the jewelry will be sold, he said.

“Zircons are an unsung hero in the jewelry world,” according to Ray Griffiths, a designer based in New York whose work typically features his signature Crownwork style, an openwork pattern often accented with colored stones. “The saturation of the color in zircon — that’s what gives them just that sense of luxury that I just love.”

And zircon’s distinct optical properties also draw Mr. Griffiths. “It’s brighter than diamond because of the birefringence of the material,” he said, referring to its ability to split a single ray of light into two. The phenomenon also “softens out the facet edges and gives the stones a shimmer and a glow rather than the crispness that diamonds or most stones have.”

Margot McKinney, a fourth-generation jeweler who has a namesake atelier in Brisbane, Australia, and is sold at Neiman Marcus and Bergdorf Goodman in the United States, makes jewels with zircons as a focal point — a cocktail ring with a stone weighing more than 52 carats, for instance — and also combines them with other stones.

She recently completed a necklace and coordinating earrings featuring a collage of stones that includes opals, blue zircons, pistachio green pearls and tsavorite. “Because it has such a high refractive index, it’s very bright,” Ms. McKinney said of the zircon. “I think it’s a perfect foil for the opal.”

Lots of Confusion

It is essential for retailers to make sure clients understand the particular properties of zircons, said Paul Schneider, owner of the Twist jewelry boutiques in Seattle and Portland, Ore. His boutiques offer pieces featuring zircon from designers such as Mallary Marks and Brent Neale.

“It’s really important to us to tell the whole story of the piece even if the client doesn’t necessarily care,” he said. “It’s part of our obligation, to inform them, especially with something like a zircon, because it’s really easily confused with other stones, like topaz or even sapphire. They’re so clear, people think that they’re not even real, that they’re lab-grown.”

Once upon a time, Katerina Perez, a London-based jewelry influencer, was among the multitudes confused by the gemstone’s name.

“At the beginning of my writing career, I instantly associated zircon with cubic zirconia, but when I did my gemological course, I learned otherwise,” Ms. Perez said. “The existence of a synthetic with a similar name doesn’t work in the favor of zircon.”

Now she numbers among the stone’s fans. Her jewelry collection includes a single oversized butterfly earring that does double duty as a pendant, designed by Susanna Gay for Filippo G&G, the Geneva gem and jewelry business owned by Ms. Gay’s brother, Filippo.

Composed of titanium with pavé-set diamond accents, the piece has a 12-carat blue zircon at its center. “I bought the earring for the look — not necessary because it’s a zircon. I love blues and greens; the zircon was the cherry on top,” Ms. Perez said. “The sparkle is very special.”

“It’s a little more intense than aquamarine,” she said. “It’s got a green undertone that’s different than topaz; it doesn’t look like anything else.”

The current moment in the jewelry trend cycle works to the advantage of zircons and their particular color palette, according to Ming Lampson, whose namesake company, Ming, in London, produces 30 to 40 one-of-a-kind pieces a year. “Now is a moment for yellow gold,” Ms. Lampson said. “Yellow and brown zircons look so good in it — they really suit yellow gold.”

Her current offerings include a pair of gold earrings featuring 11-millimeter bezel-set zircons in a similar golden hue. “Finding stones so like the color of gold was really interesting to me,” she said.

Ms. Lampson noted that the once difficult-to-source stones have become more available, partially as a response to demand. “In the past, when I would ask stone dealers for zircons, they would ask, ‘Why do you want one of those?’ whereas now they’re readily showing me natural zircons.”

A broader appreciation for colored gems of every stripe has improved their reputation, she said. “People are much more open to all gemstones than ever before.”

The Soft Side

Working with stones that aren’t widely known is a point of distinction in the work of Mia Moross, founder of the brand The One I Love NYC. “A lot of emerging designers are trying to evolve and create weirder stuff and work with different stones that haven’t been heard of as much,” she said. “At least, that’s what I’m trying to do.”

She compares the recent reversal of fortune for the zircon to that of another colored gem whose reputation has made a precipitous climb: spinel. Once known as “the great impostor” because it was often mistaken for a ruby, spinels now are sought after in their own right.

“Spinel got a bad rap for a while,” Ms. Moross said, “until people realized that there were several among the Crown Jewels” of Britain.

She works exclusively with vintage stones, recutting and polishing them as needed, and generally uses zircons for rings and pendants because the settings can provide some protection.

“Zircon is a 7.5 on the Mohs scale,” she said, referring to the standard measure for mineral hardness, “which is softer than precious gemstones. In my personal opinion, it needs to be bezel set.”

James de Givenchy takes a similar approach with zircons as creative director of Taffin, his jewelry house with offices in New York and Miami that offers limited production of one-of-a-kind pieces. “I use them in cocktail rings because they’re rings that are often not going to be used every day,” he said. “I’ve used them as pendants because they’re very safe, necklaces. I made a bracelet composed of a collection of blue zircons taken from an Art Deco necklace.”

A designer who has made his name by combining precious gems with unexpected materials — old mine diamonds and leather or sapphires and ceramic — Mr. de Givenchy worked with zircons from the start of his business about 20 years ago. “I thought it was nice to use zircons because they were beautiful; the brightness and dispersion of light in the stone is just magical,” he said. “And people didn’t know what they were. Zircons are probably one of the oldest stones on the planet.”

In 2014, a zircon found in Australia was determined to be about 4.4 billion years old, the oldest mineral that has been dated so far.

Mr. de Givenchy said he had noticed a gradually increasing awareness of the stone and with it, its prices to jewelry makers. “There was a time when they were $10 per carat and now I’m seeing them at $300, $350 per carat,” he said. “It’s insane. The moment the market picks up on something, it’s the new frontier.”

Mr. Gay of the gem dealership Filippo G&G said he also had observed a significant increase in the price of zircon. “The prices doubled recently — maybe within the last year,” he said, citing both increased demand and somewhat limited supply of the stones, particularly those of more than 40 carats. “They are mostly found in Cambodia and Tanzania. Only a few people have their hands on zircon.”

According to Rebecca Shukan, director of sales for Omi Privé, a Los Angeles company that offers both loose gems and jewelry, the color, size and clarity of zircons determine their prices.

“Most of the zircon gemstones being used for jewelry range from four to seven carats,” she said. “Fine-gem-quality zircon that is eye-clean, with even coloration, retails for $800 to $900 per carat. Once you start looking for stones that are 20 carats and above, you will see a retail price closer to $1,500 per carat.”

In the Name

Although Mr. de Givenchy’s clients don’t resist buying zircons — “If you’re working one-on-one with clients, it’s easy to explain. It’s never been an issue for me” — he does see the name as a shortcoming. “It’s a horrible name,” he said. “It would be a fun thing to rename that stone.”

Indeed, renaming gemstones that have less-than-palatable mineral labels is not that unusual. “Tanzanite was called blue zoisite,” Mr. Wennick of Wennick-Lefèvre said. The bright green type of grossular garnet has a similar story. “It was called grossular garnet. That was very hard to say, so it was changed to tsavorite. Zircon is a lovely name, but I think it will always be associated with cubic zirconia to most people.”

George F. Kunz, an influential American mineralogist of the late 19th and early 20th century and a zircon enthusiast, advocated changing the stone’s name to “starlite,” to emphasize its fiery qualities. But, obviously, his effort didn’t take.

Mr. Gay bemoaned that outcome: “If the name had been changed then, everything could have been different.”