High jewelry houses traditionally have used Couture Week as a time to present their latest creations to some of the wealthiest customers in the world. This week, however, Van Cleef & Arpels took the opposite tack, traveling back in time instead.

For four days, the Place Vendôme jeweler transformed the salons of the 18th-century Hôtel de Mercy-Argenteau, its jewelry school’s newly refurbished annex, into a showcase for some 70 pieces from its own collection. (The house’s patrimony department, which began reacquiring some special creations in the 1970s, now holds more than 2,700 pieces.) The glittering showcase was viewable by couture clients and the press by appointment only.

The exhibition was staged to resemble the pages of a new book, “The Van Cleef & Arpels Collection (1906-1953).” The first of two volumes to be published by the French art book specialist Atelier EXB, it includes images of 680 jewels, watches and other precious objects, as well as some archival documents.

Alexandrine Maviel-Sonet, the house’s patrimony and exhibitions director, said her team spent more than three years doing research and compiling the book like a catalogue raisonné, a term for a comprehensive, annotated listing of an artist’s work.

“The idea was to present a collection that’s significant,” she said. “We are trying to show, like an artist, that our jewels are art pieces: they are part of the decorative arts, but also art in general.”

Important designs from the house’s earliest creative boom were on show, including a supple diamond-covered link bracelet with three imposing emerald cabochons, and an articulated cuff bracelet with roses created in diamonds, rubies, emeralds and onyx. Both of those pieces were also presented nearly a century ago, at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, where Van Cleef & Arpels was awarded the grand prize for jewelry.

The house’s signature motifs were represented, too, including ballerinas with gem-encrusted skirts and birds with emerald cabochon bellies, as well as flowers pavéd with precious stones in the Mystery Set technique. That gem-setting method, which renders the metal framework invisible, was invented and patented by the house in 1933.

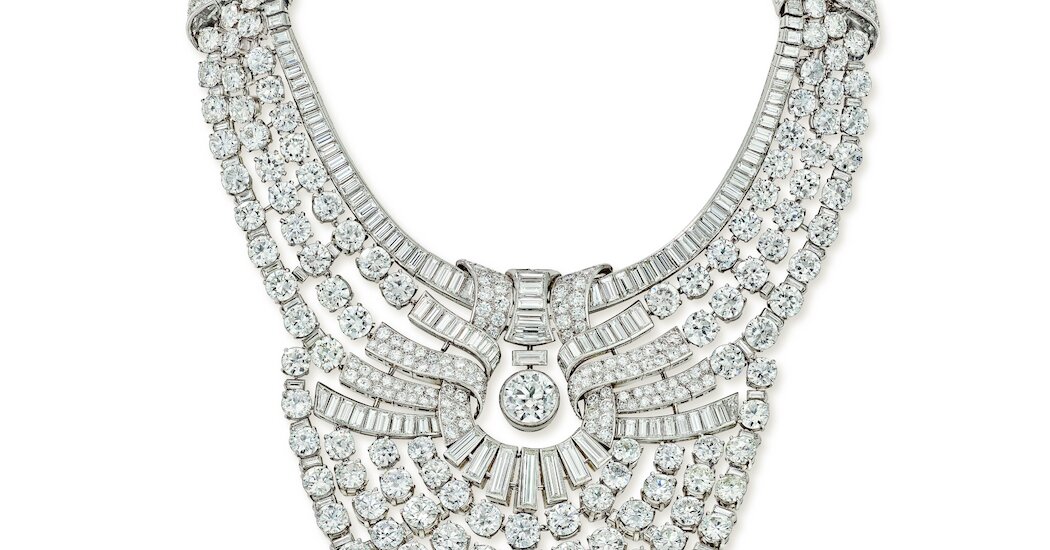

The show included a couple of royal commissions, such as a platinum and diamond collaret worn in 1939 by Queen Nazli of Egypt, the queen mother. The creation — a big piece, shaped like a bib necklace — was included in a section on the jeweler’s overseas expansion, notably to New York, starting in the late 1930s.

Ms. Maviel-Sonet said the deep dives into the house’s history had led to some surprises, including information on how the house’s artisans used diamonds to mimic shagreen, a natural hide, often from a shark or stingray, which was very popular in the Art Deco period. Those details, however, are being saved for the next volume, which is to cover the second half of the 20th century. It is scheduled for 2026, to coincide with the jeweler’s 120th anniversary.