One of the biggest bangs heard in the history of wine, on a May evening in 1976, caused barely a ripple in the home of Warren and Barbara Winiarski, the proprietors of Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars in Napa Valley.

The day before, a 1973 Stag’s Leap cabernet sauvignon had won a tasting in Paris that pitted some of the greatest French wines against bottles from upstart California. But when a friend who had been in France called Ms. Winiarski (pronounced win-ee-YAR-skee) to notify her of the victory, she had only a vague idea what the caller was talking about. So she dialed her husband, who was away on business. He, too, couldn’t remember any tasting or grasp its potential importance.

“That’s nice,” he said.

The tasting itself might have remained as inconsequential as it seemed to the Winiarskis if George M. Taber, a reporter for Time magazine, had not been on hand to witness it. His article, “Judgment of Paris,” trumpeted a shocking David-over-Goliath triumph that gave the fledgling California wine business a swift dose of international credibility.

“The unthinkable happened: California defeated all Gaul,” Mr. Taber wrote.

Almost 50 years later, marketers are still using that tasting, re-enacting it countless times, to sell California wines around the world.

It was certainly momentous for the Winiarskis and Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, a startup that was virtually unknown before the tasting. There had been little demand for its ’73 cabernet, only the winery’s second vintage, but that was about to change.

“The phone started to ring pretty quickly,” Mr. Winiarski recalled in 1983. It continued to ring for years.

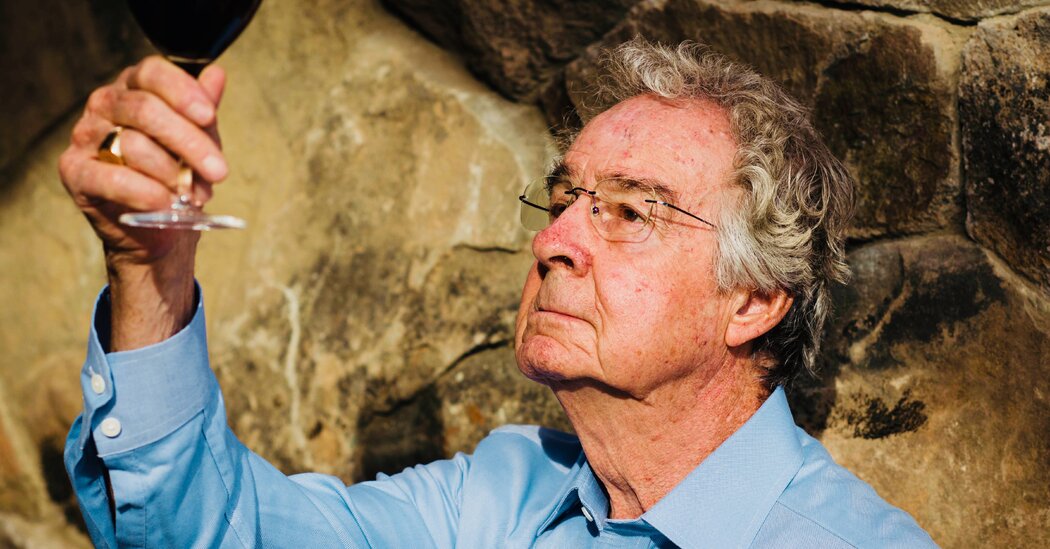

He died on June 7 at his home in Napa, Calif., a representative for him said. He was 95.

For Mr. Winiarski, who began working in wine only at 35, the Paris victory was an abrupt change of fortune. He had been a wine-obsessed lecturer in the humanities at the University of Chicago in 1964 when he and his wife decided to leave academia and try their hand at the wine business.

They packed their belongings in a U-Haul trailer, loaded their two young children into a Chevrolet station wagon and set out for Napa Valley, which back then was a sleepy, isolated agricultural community where walnuts and prunes were more common than wine grapes.

With few resources but an invitation to work the harvest at Chateau Souverain, a winery on Howell Mountain, they arrived in August 1964 and set up house in a cabin nearby with a wood-burning stove.

As the second man in a two-man operation at Souverain, Mr. Winiarski learned the basics of grape-growing and winemaking while mastering the menial tasks of stacking crates and keeping the winery scrupulously clean. But his academic training was never far behind. He studied all aspects of farming and winemaking, developing over time a philosophy of wine that emphasized balance, harmony, finesse and elegance rather than weight and power.

Within a decade he was the proprietor of his own winery — and making a wine that would shock the world.

After the tasting, Stag’s Leap became one of Napa Valley’s leading lights, an attraction for tourists and connoisseurs alike as the region turned into a wine wonderland. Mr. Winiarski acquired more vineyards and expanded the business, growing from producing roughly 1,800 cases of wine in 1973 to 150,000 in 2006.

In 2007, at 78 and with none of his children willing to carry on at Stag’s Leap, Mr. Winiarski sold the winery for $185 million. Current vintages of the $6 bottle that won the tasting now sell for about $250.

Warren Paul Winiarski was born on Oct. 22, 1928, in the Bucktown section of Chicago to Stephen and Lottie (Lacki) Winiarski, who ran a livery business in their largely Polish neighborhood. While the Winiarskis — the name translates roughly to “from a winemaker” in Polish — did not drink wine regularly, Warren’s father made his own wine with honey, fruit or dandelions, and the family would drink it on special occasions. Mr. Winiarski later recalled listening to the bubbling of wine fermenting in his father’s basement.

As a youth, books and philosophy interested Warren more than wine. He studied the humanities at St. John’s College, in Annapolis, Md., where he also met Barbara Dvorak, whom he later married.

He is survived by their three children, Kasia, Stephen and Julia, and six grandchildren. Ms. Winiarski died in 2021.

After graduating from St. John’s, Mr. Winiarski studied political science at the University of Chicago. He spent a year in Italy, where, while researching Machiavelli and other Italian renaissance figures, he became part of a close-knit group in which food and wine played central roles.

He returned to Chicago but retained his fascination with wine and food. It wasn’t until a friend brought him a bottle of American wine that he began to envision himself making wine and living a more agrarian life.

The transition to Napa Valley was not easy for the Winiarskis. Their first effort to plant a vineyard — three acres on a 15-acre property high up on Howell Mountain — did not succeed. They sold it, cutting their losses.

Having absorbed all he could at Souverain, Mr. Winiarski in 1966 took a job at Robert Mondavi Winery, a new project that was the most ambitious winery to be built in California since Prohibition and which set the tone for the Napa Valley to come.

Mr. Winiarski was hired as assistant winemaker, but with Michael Mondavi, Robert’s elder son, who was the winemaker, serving in the military, Mr. Winiarski was essentially in charge of the wine.

Going from Souverain, an artisanal, almost primitive operation, to Mondavi, a big, futuristic winery, was a huge transition, but after two vintages, with Michael Mondavi back in the fold, Mr. Winiarski felt ready to run his own show.

He had spent his spare time traveling the valley in search of potential sites for a vineyard. Unlike many of his colleagues, who believed that the choice of grapes and the winemaking were most important, Mr. Winiarski was convinced that it was essential to select the right site, and that the best sites could convey particular characteristics in the wines. In this sense he was an early proponent in Napa of the French notion of terroir.

He found the site he was looking for in Stag’s Leap, an area in the southern part of the valley, where he was impressed by a wine made by Nathan Fay, a farmer and home winemaker. After putting together a group of investors, Mr. Winiarski bought 50 acres adjoining Mr. Fay’s farm. He also befriended Mr. Fay, buying grapes for what would be one of three top wines that Stag’s Leap would produce. Two were single-vineyard wines, Fay and S.L.V., as wines from the original Stag’s Leap vineyard were labeled. The third, Cask 23, was a blend made only in exceptional vintages.

After selling his winery, Mr. Winiarski continued to farm grapes and became a philanthropist, making large contributions to the Smithsonian Institution, where he was honored in 2019 for his contributions to American winemaking, and to St. Michael’s College, where, as a former humanities scholar, he taught in its summer classics program for many years.

“You always have this dream that you’re going to do your own thing,” he told The New York Times in 1983. “In retrospect, it was an extremely imprudent thing. But we rode the crest of a wave. Yes, I had it all planned out, but I couldn’t really foresee what would happen.”