Anna Parker found the image online: a teal onesie with a handwritten note pinned to the front. “Someday,” it read.

It was a word Ms. Parker kept repeating to herself. She and her husband have been trying for four years to have a second baby and are now going through in vitro fertilization. She posted the photo on her Facebook page in January, along with a message about her weight, which was the highest it had been since her first pregnancy. Her blood sugar, too, was troublingly high.

“I’m scared to go into pregnancy,” she wrote in the Facebook post. “I’m so afraid being unhealthy will make me miscarry.”

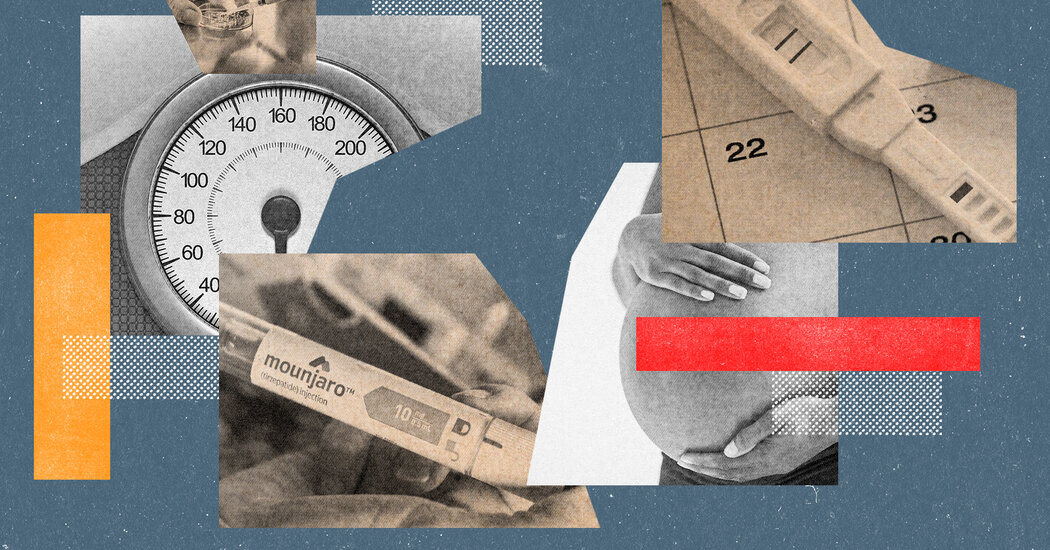

Ms. Parker, 38, wrote in the post that she had just started taking a new diabetes medication, Mounjaro, which is also widely used for weight loss. She felt “miserable” after her first few doses, Ms. Parker said in an interview. She was recently cleaning out her 5-year-old son’s lunch box, and the smell of ketchup from his dinosaur-shaped chicken nuggets made her vomit into the sink.

Doctors say they are seeing more women like Ms. Parker try weight-loss medications in the hopes of having a healthy pregnancy, or of conceiving in the first place. Women with obesity are sometimes advised to lose weight before pregnancy, because some research suggests that excess weight can make it harder to get pregnant and can increase the risk of miscarriage and pregnancy complications.

For patients on these drugs, the side effects are only one challenge. What some said they find more alarming is just how little information there is on the risks of taking these drugs before or during pregnancy. With next to no data on Mounjaro, Ozempic and similar medications during pregnancy, doctors typically recommend that women stop taking them at least two months before trying to conceive.

This leaves women with a narrow window: Stay on the drugs long enough to see results, but not so long they might put a fetus at risk.

For “a journey as unpredictable and individualized as fertility,” that can be extraordinarily difficult to navigate, said Dr. Akua Nuako, a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital focused on obesity and weight-loss medications.

Navigating new unknowns

While some patients hope these medications might help them conceive, it’s not clear yet whether weight loss always makes it easier to get pregnant. In theory, the body ovulates most regularly and reliably if someone is not over- or underweight, said Dr. Jessica Chan, a reproductive endocrinologist at Cedars-Sinai.

That’s one reason that fertility doctors and clinics sometimes advise patients to lose weight. Some clinics will not even treat patients with a body mass index over 40. For these patients in particular, weight-loss drugs could be a valuable tool, fertility doctors said. Researchers are also studying whether these drugs could help women with polycystic ovary syndrome, a leading cause of infertility that leads to irregular periods and is more common in women with obesity.

“I do counsel patients, especially if they aren’t on contraception, that with weight loss, especially a significant amount of weight loss, it can improve ovulation,” said Dr. Sarah Lassey, a maternal fetal medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She said she has consulted over 100 patients who are on weight-loss drugs and trying to plan for pregnancy.

Part of the appeal to patients like Ms. Parker is how fast these drugs can work. For women 35 and older, who are already more likely to have trouble getting pregnant, that promise can be especially enticing.

“My husband and I are not getting any younger,” Ms. Parker said. “So I need to do this quick.”

And there are the risks of what Ms. Parker views as the alternative: entering a pregnancy with excess weight or high blood sugar.

While many miscarriages are the result of chromosomal abnormalities, women with uncontrolled diabetes do have a higher risk of miscarriage. They are also more likely to develop pre-eclampsia or have a preterm birth. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that providers encourage women with obesity to lose weight before pregnancy. Studies have suggested a link between obesity and an increased risk of birth defects, stillbirth, preterm birth and other concerns, said Dr. Andrea Shields, the vice chair of the organization’s committee on clinical guidelines for obstetric care.

It’s not clear whether obesity directly causes those issues, or whether other lifestyle factors or health conditions, like diabetes, may play a role.

The conversation around weight, fertility and pregnancy is “already complicated and stigmatized,” said Dr. Nuako, the doctor at Massachusetts General Hospital. These drugs, she said, just add “another level of difficulty.”

‘Holding our breath’

When a nurse practitioner prescribed Mounjaro to Marcela Romero to lower her blood sugar in November 2022, she bristled at the idea of taking a “diet pill,” she said. But Ms. Romero had been trying to get pregnant for three years. She was planning to start in vitro fertilization and was worried about her weight and the risk of gestational diabetes.

On Mounjaro, she stopped thinking about food, lost 10 pounds in a month and saw her blood sugar drop. But she also felt a shift in her body she couldn’t place. Hours after she injected her fourth weekly dose, she took a pregnancy test. When two pink lines popped up, she ran down the stairs of her house in Fort Myers, Fla., and held it up to her father, who was visiting from Colombia. He started crying on the spot.

Ms. Romero was thrilled, but also terrified that she had taken Mounjaro while pregnant. “My first thought was, well this is great and everything, but do we know, are there any complications with pregnancy? Are there any defects kids are born with?” she said. She stopped taking the drug right away.

She tried not to worry. But she couldn’t shake the fear, and she found little that could ease her concerns.

“Of course there’s no information, because it’s so new,” she said.

Like in many clinical trials, studies of these medications excluded women who were pregnant. The companies that make these medications have said they plan to monitor pregnancy outcomes. One of the few human studies so far found that women with Type 2 diabetes who were taking these drugs when they conceived or in early pregnancy did not have a higher risk of delivering babies with major congenital malformations than those who took insulin.

But animal studies have suggested that the medications might harm a fetus. That’s of particular concern if people are taking the drugs without realizing they’re pregnant. And experts also noted that some of these medications — specifically, Mounjaro and the weight-loss drug Zepbound, which contain the same compound — may also make birth control pills less effective at certain points in the dosing schedule.

Until there is more research in humans, Dr. Shields said, “we’re all just kind of holding our breath.”

Ms. Parker plans to stay on Mounjaro long enough to lose 40 pounds, she said, and then undergo the embryo implantation. Still, she worries about the possible long-term effects of the medication on her body. “It is kind of concerning,” she said. “You think, ‘is this just the ’90s, where we’re taking diet pills you get from the gas station?’”

Some doctors also said they were concerned about what may happen in the window between patients going off these medications and getting pregnant. Patients often regain weight after they stop the drugs and can end up weight cycling, a term doctors use for fluctuations in weight that may strain the cardiovascular system.

For patients, any choice can feel like a risk during pregnancy. Ms. Romero felt like she reached a point where she couldn’t physically contain all her worry. “I was like, I’m going to trust the universe,” she said. “It is what it is. Because at this point, I can’t do anything, right?”

In September, she gave birth to a healthy baby girl.

Ms. Parker finds herself sometimes combing through Facebook posts from other women who have gotten pregnant after taking these drugs. With so little data to look at, all she has are these anecdotes. “Maybe the weight loss outweighs the cons,” she said. “But I don’t know if we know about the cons yet.”