The Maryland Legislature this weekend passed two sweeping privacy bills that aim to restrict how powerful tech platforms can harvest and use the personal data of consumers and young people — despite strong objections from industry trade groups representing giants like Amazon, Google and Meta.

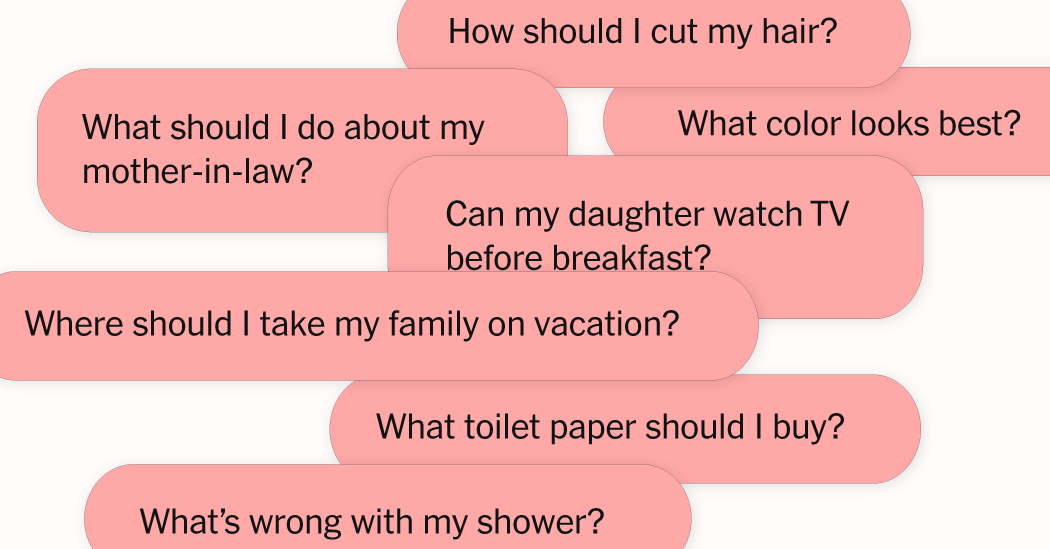

One bill, the Maryland Online Data Privacy Act, would impose wide-ranging restrictions on how companies may collect and use the personal data of consumers in the state. The other, the Maryland Kids Code, would prohibit certain social media, video game and other online platforms from tracking people under 18 and from using manipulative techniques — like auto-playing videos or bombarding children with notifications — to keep young people glued online.

“We are making a statement to the tech industry, and to Marylanders, that we need to rein in some of this data gathering,” said Delegate Sara Love, a Democratic member of the Maryland House of Delegates. Ms. Love, who sponsored the consumer bill and cosponsored the children’s bill, described the passage of the two measures as a “huge” privacy milestone, adding: “We need to put up some guardrails to protect our consumers.”

The new rules require approval by Gov. Wes Moore of Maryland, a Democrat, who has not taken a public stance on the measures.

With the passage of the bills, Maryland joins a small number of states including California, Connecticut, Texas and Utah that have enacted both comprehensive privacy legislation and children’s online privacy or social media safeguards. But the tech industry has challenged some of the new laws.

Over the last year, NetChoice, a tech industry trade group representing Amazon, Google and Meta, has successfully sued to halt children’s online privacy or social media restrictions in several states, arguing that the laws violated its members’ constitutional rights to freely distribute information.

NetChoice did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The Maryland Kids Code is modeled on a 2022 California law, called the Age-Appropriate Design Code Act. Like the California law, the Maryland bill would require certain social media and video game platforms to turn on the highest privacy settings by default for minors. It would also prohibit the services from unnecessarily profiling minors and collecting their precise locations.

A federal judge in California, however, has temporarily blocked that state’s children’s code law, ruling in favor of NetChoice on free speech grounds. (The New York Times and the Student Press Law Center filed a joint friend-of-the-court brief last year in the California case in support of NetChoice, arguing that the law could limit newsworthy content available to students.)

NetChoice has similarly objected to the Maryland Kids Code. In testimony last year opposing an earlier version of the bill, Carl Szabo, the general counsel of NetChoice, argued that it impinged on companies’ rights to freely distribute information as well as the rights of minors and adults to freely obtain information.

Maryland lawmakers say they have since worked with constitutional experts and amended it to address free speech concerns. The bill passed unanimously.

“We are technically the second state to pass a Kids Code,” said Delegate Jared Solomon, a Democratic state lawmaker who sponsored the children’s code bill. “But we are hoping to be the first state to withstand the inevitable court challenge that we know is coming.”

Several other tech industry trade groups have strongly opposed the other bill passed on Saturday, the Maryland Online Data Privacy Act.

That bill would require companies to minimize the data they collect about online consumers. It would also prohibit online services from collecting or sharing intimate personal information — such as data on ethnicity, religion, health, sexual orientation, precise location, biometrics or immigration status — unless it is “strictly necessary.”