In April, a New York start-up called Runway AI unveiled technology that let people generate videos, like a cow at a birthday party or a dog chatting on a smartphone, simply by typing a sentence into a box on a computer screen.

The four-second videos were blurry, choppy, distorted and disturbing. But they were a clear sign that artificial intelligence technologies would generate increasingly convincing videos in the months and years to come.

Just 10 months later, the San Francisco start-up OpenAI has unveiled a similar system that creates videos that look as if they were lifted from a Hollywood movie. A demonstration included short videos — created in minutes — of woolly mammoths trotting through a snowy meadow, a monster gazing at a melting candle and a Tokyo street scene seemingly shot by a camera swooping across the city.

OpenAI, the company behind the ChatGPT chatbot and the still-image generator DALL-E, is among the many companies racing to improve this kind of instant video generator, including start-ups like Runway and tech giants like Google and Meta, the owner of Facebook and Instagram. The technology could speed the work of seasoned moviemakers, while replacing less experienced digital artists entirely.

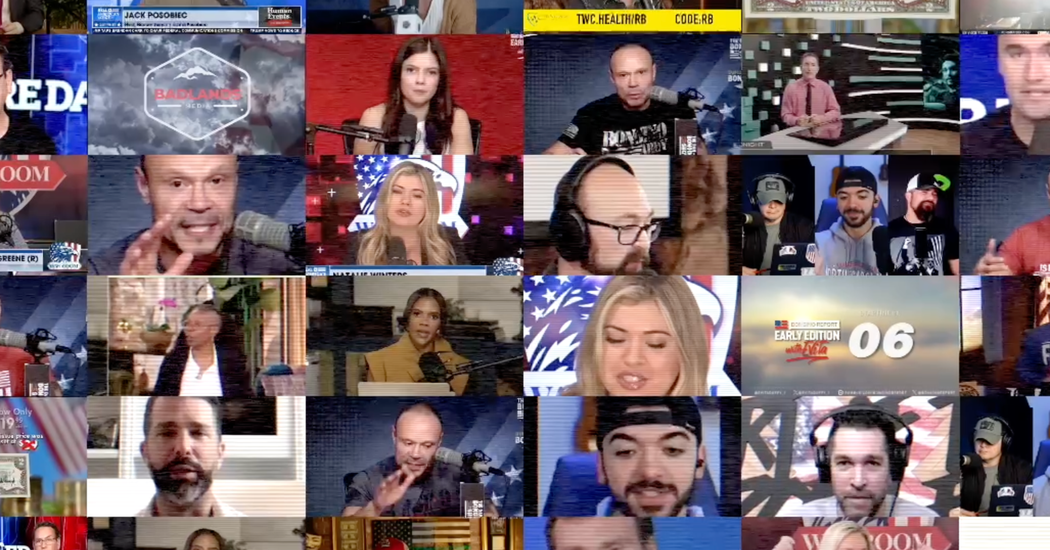

It could also become a quick and inexpensive way of creating online disinformation, making it even harder to tell what’s real on the internet.

“I am absolutely terrified that this kind of thing will sway a narrowly contested election,” said Oren Etzioni, a professor at the University of Washington who specializes in artificial intelligence. He is also the founder of True Media, a nonprofit working to identify disinformation online in political campaigns.

OpenAI calls its new system Sora, after the Japanese word for sky. The team behind the technology, including the researchers Tim Brooks and Bill Peebles, chose the name because it “evokes the idea of limitless creative potential.”

In an interview, they also said the company was not yet releasing Sora to the public because it was still working to understand the system’s dangers. Instead, OpenAI is sharing the technology with a small group of academics and other outside researchers who will “red team” it, a term for looking for ways it can be misused.

“The intention here is to give a preview of what is on the horizon, so that people can see the capabilities of this technology — and we can get feedback,” Dr. Brooks said.

OpenAI is already tagging videos produced by the system with watermarks that identify them as being generated by A.I. But the company acknowledges that these can be removed. They can also be difficult to spot. (The New York Times added “Generated by A.I.” watermarks to the videos with this story.)

The system is an example of generative A.I., which can instantly create text, images and sounds. Like other generative A.I. technologies, OpenAI’s system learns by analyzing digital data — in this case, videos and captions describing what those videos contain.

OpenAI declined to say how many videos the system learned from or where they came from, except to say the training included both publicly available videos and videos that were licensed from copyright holders. The company says little about the data used to train its technologies, most likely because it wants to maintain an advantage over competitors — and has been sued multiple times for using copyrighted material.

(The New York Times sued OpenAI and its partner, Microsoft, in December, claiming copyright infringement of news content related to A.I. systems.)

Sora generates videos in response to short descriptions, like “a gorgeously rendered papercraft world of a coral reef, rife with colorful fish and sea creatures.” Though the videos can be impressive, they are not always perfect and may include strange and illogical images. The system, for example, recently generated a video of someone eating a cookie — but the cookie never got any smaller.

DALL-E, Midjourney and other still-image generators have improved so quickly over the past few years that they are now producing images nearly indistinguishable from photographs. This has made it harder to identify disinformation online, and many digital artists are complaining that it has made it harder for them to find work.

“We all laughed in 2022 when Midjourney first came out and said, ‘Oh, that’s cute,’” said Reid Southen, a movie concept artist in Michigan. “Now people are losing their jobs to Midjourney.”