Product placement, one of the oldest tricks in advertisers’ toolbox, is getting an A.I. makeover.

New technology has made it easier to insert digital, realistic-looking versions of soda cans and shampoo onto the tables and walls of videos on YouTube and TikTok. And a growing group of creators and advertisers is grabbing at the chance for an additional revenue stream.

A recent TikTok from the dancer Melissa Becraft featured a poster for Bubly, the sparkling-water brand owned by PepsiCo, hanging on the wall of her apartment as she shimmied to a Shakira song. A duo known as HiveMind chatted about bands while an animated can of Starry soda, another brand owned by PepsiCo, landed on a table between them. And a YouTube video of the “AsianBossGirl” podcast recently displayed a table of Garnier hair products.

Virtual product placements have been offered by start-ups and streaming services like Amazon Prime and NBC’s Peacock in recent years. But a recent wave of them on social media, in which brief, animated messages disclosing the sponsorships appear on the videos themselves, is the work of a start-up called Rembrand.

The ads provide a glimpse into one way A.I. might shape advertising in the future, especially as marketers look to reach younger viewers who are apt to skip or ignore standard ads.

Rembrand’s executives say their technology could transform product placements, which have often been used to cut production costs on bigger projects and can take weeks, months or sometimes years to negotiate.

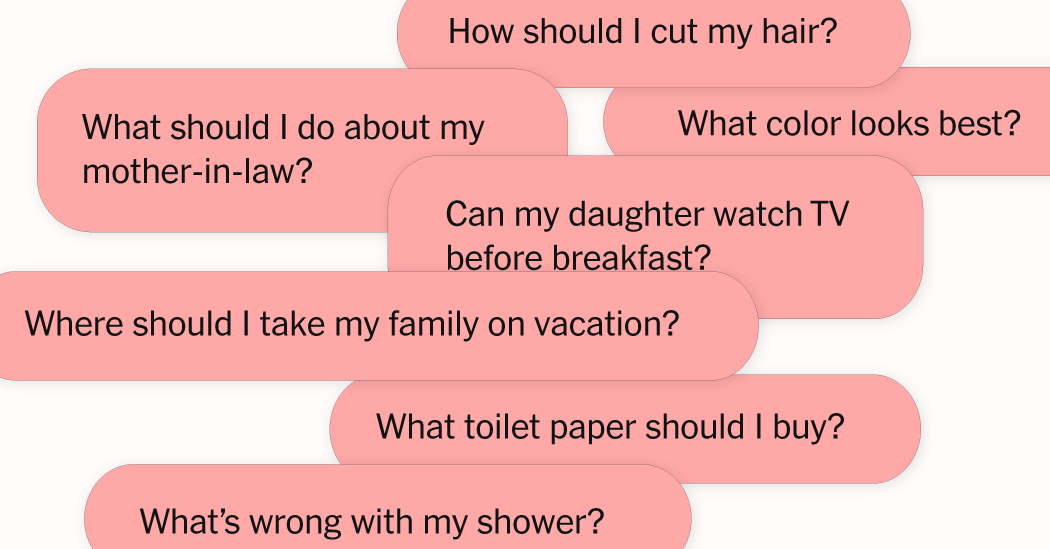

For creators, it’s a way to make money from advertisers without physically handling products or discussing them.

“This feels like I’m making my own genuine content, but it doesn’t scream that I’m making an ad,” said Ms. Becraft, 28, who has made two TikTok videos that featured Bubly. “There’s no obligation for me to talk about it.”

Product placements in the United States are estimated to be a nearly $23 billion industry, according to PQ Media, a research firm. It has become increasingly appealing to advertisers, which have grown worried about consumers skipping commercials or the ads before YouTube videos.

The shifting viewership to social platforms and advances in technology have opened a new frontier for this work, moving it beyond getting Coca-Cola cups on the “American Idol” judges’ table or cereal brands into WB shows.

Rembrand, which has 42 employees and is based in Palo Alto, Calif., believes it’s on the forefront of these changes. It raised $14 million in seed funding from the likes of Greycroft and the venture arms of UTA Ventures and L’Oreal since it was created in 2022. One of its founders, Omar Tawakol, 55, spent years in programmatic advertising and is best known for founding and selling BlueKai — which helped marketers track users’ online behavior for ad targeting — to Oracle in 2014.

Mr. Tawakol said he saw an opportunity to use A.I. to insert virtual products in influencer videos and make it a fast and easy ad buy.

Rembrand uses a form of generative A.I. that can “take an existing scene and figure out how to put a product in it,” Mr. Tawakol said. “The product has to look exactly right — Pepsi is not going to be forgiving if you screw with their logo,” he added.

The company “had to train the laws of physics into the network,” Mr. Tawakol said, so that objects would properly respond to things like light, camera distance and motion. Rembrand started placements with podcasts on YouTube because “they tended to be indoors, they tended to have fixed cameras, and they tended to have a table and a wall,” he said.

It then expanded to LinkedIn and TikTok; Instagram is next. (The company said it went with the name Rembrand — an allusion to the Dutch artist, who spelled it Rembrandt — because it wanted an artistic bent while also sounding like shorthand for “remember the brand.”)

Rembrand is still asking creators like Ms. Becraft to film indoors as they improve the technology. “The things I’m more famous for are dancing outside in the rain and dancing in Times Square,” she said. “They told me that if you do that our technology might have a heart attack.”

The placements are not as subtle as the ones in TV shows. Starry and Bubly cans wiggle before entering videos, and logos hover above them. The company shared a demo in which a digitized Tide Pen danced onto a podcast host’s shirt and wiped away a stain before vanishing, “Fantasia” style. The company experimented with “what animations were acceptable,” after realizing they could spike attention on the products, said Cory Treffiletti, 50, Rembrand’s chief marketing officer.

Madison Luscombe, chief marketing officer of the Creator Society, an agency that works with Ms. Becraft, said that while the use of A.I.-generated product placement was in its early days, the deals could be valuable for “entertainment creators” who are focused on performing, podcasting or playing games, and aren’t necessarily approached by brands as often to extol mascara or new snacks to their fans.

Advertisers use Rembrand’s marketplace to connect with more than 1,000 creators from agencies it works with. Creators upload their videos to its platform and receive them within 24 hours with the product placements. Rembrand has someone check for quality and someone else for how the brand appears. Then creators upload the clips and eventually get paid from the brands based on video views. Rembrand declined to share specific figures around payouts.

The company said it expected to turn into a “self-service platform” by the middle of this year, where any creator or brand could connect and run digital product placement campaigns without Rembrand’s involvement.

When asked why YouTube, TikTok and Instagram wouldn’t just offer this option directly to creators on their platforms, Mr. Tawakol said he would “love” if they wanted to work with him. “I designed my business to integrate it with platforms,” he said. “We want to be the world’s best at this one very specific problem.”